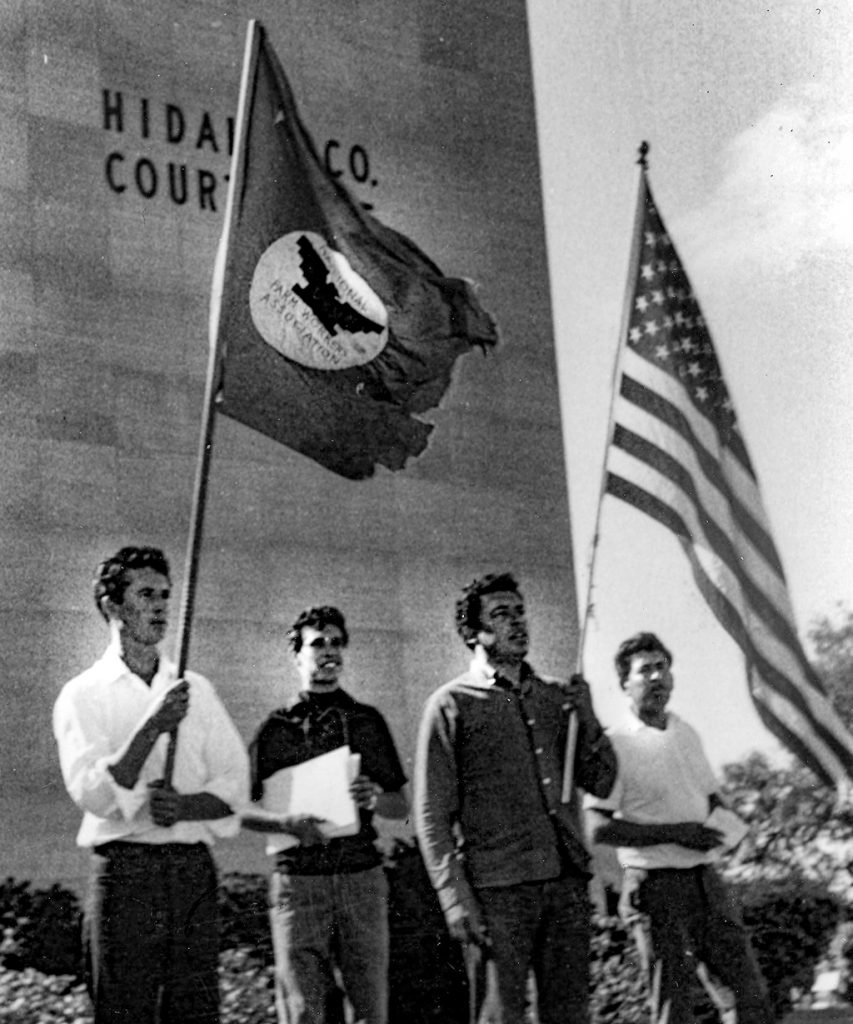

Featured: Leaders gathered in front of the Hidalgo County Courthouse in Edinburg in support of migrant farmworkers from the Rio Grande Valley during the 1966 melon strike that featured a walk from Starr County through Edinburg to Austin seeking better working conditions and pay for workers, which helped ignite the Chicano Movement in Texas.

Photograph Courtesy LA UNÍON DEL PUEBLO ENTERO (LUPE)

Edinburg and The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on Friday, September 9, 2016, will serve as sites for the 50th anniversary celebration of the 1966 melon strike by Texas farmworkers that resulted in more civil rights for labor and Hispanics, and helped ignite the Chicano Movement in Texas.The event, which is being hosted by the United Farmworkers, will begin at 9 a.m. at the courtyard of the International Trade and Technology Building at the Edinburg university, 1201 West University Drive. At 9:30 a.m., participants will continue with a march to the Edinburg City Hall Courtyard, followed by a program inside the adjacent City Auditorium, located at 415 W. University Drive, beginning at 10 a.m. The announcement of the upcoming celebration came on Tuesday, August 23, 2016, during the public comment portion of the Edinburg City Council meeting at Edinburg City Hall. As part of that news, Mayor Richard García and the City Council – Mayor Pro Tem Richard Molina, Councilmember Homer Jasso, Jr., Councilmember J.R. Betancourt, and Councilmember David Torres – unanimously approved a city proclamation recognizing the impact and importance of the 1966 melon strike on the Valley and Texas. García also serves as a member of the Board of Directors of the Edinburg Economic Development Corporation, which is the jobs-creation arm of the Mayor and Edinburg City Council.

••••••

Edinburg, UTRGV to serve as sites on Friday, September 9, 2016 for 50th anniversary celebration of 1966 melon strike by Texas farmworkers that resulted in more rights for labor and Hispanics

By DAVID A. DÍAZ

[email protected]

Edinburg and The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on Friday, September 9, 2016, will serve as sites for the 50th anniversary celebration of the 1966 melon strike by Texas farmworkers that resulted in more civil rights for labor and Hispanics, and helped ignite the Chicano Movement in Texas.

The event, which is being hosted by the United Farmworkers, will begin at 9 a.m. at the courtyard of the International Trade and Technology Building at the Edinburg university, 1201 West University Drive. At 9:30 a.m., participants will continue with a march to the Edinburg City Hall Courtyard, followed by a program inside the adjacent City Auditorium, located at 415 W. University Drive, beginning at 10 a.m.

The announcement of the upcoming celebration came on Tuesday, August 23, 2016, during the public comment portion of the Edinburg City Council meeting at Edinburg City Hall.

As part of that news, Mayor Richard García and the City Council – Mayor Pro Tem Richard Molina, Councilmember Homer Jasso, Jr., Councilmember J.R. Betancourt, and Councilmember David Torres – unanimously approved a city proclamation recognizing the impact and importance of the 1966 melon strike on the Valley and Texas.

García also serves as a member of the Board of Directors of the Edinburg Economic Development Corporation, which is the jobs-creation arm of the Mayor and Edinburg City Council.

Agustín García, Jr., no relation to the mayor, is the Executive Director of the Edinburg EDC.

The Edinburg EDC Board of Directors is comprised of Mark Iglesias as President, Harvey Rodríguez, Jr. as Vice President, Ellie M. Torres as Secretary/Treasurer, and Mayor Richard García and Richard Rupert as Members.

“Come hear the story of the melon strikers and those who marched from Starr County to Austin in the Summer of 1966,” states a brochure by leaders with La Unión del Pueblo Entero (LUPE), which was shared with the Mayor, Edinburg City Council, and audience during the public comment segment of the city council meeting on Tuesday, August 23, 2016.

LUPE, according to its website ( http://lupenet.org), is a community union, rooted in the belief that members of the low-income community have the responsibility and the obligation to organize themselves. Through their association they begin to advocate and articulate for the issues and factors that impact their lives. LUPE has offices or a presence in San Juan, Alton, Mercedes, Pharr, and Edcouch.

Representing LUPE at the City Council meeting were Juanita Valdéz-Cox, Executive Director, Tania Chávez, M.B.A., M.A., Special Projects & Outreach Coordinator, Martha Sánchez, Community Organizing Coordinator, and John-Michael Torres, Communications Coordinator.

Guests for the 50th anniversary celebration in Edinburg of the 1966 melon strike by Texas farmworkers will feature prominent figures, including Arturo S. Rodríguez, the President of the United Farmworkers, and some of the farmworkers who participated in the melon strike, which, according to organizers of the event, “sparked the Chicano movement in Texas.”

Rodríguez, according to the UFW web site, is continuing to build the union César Chávez founded into a powerful voice for farm workers by increasing its membership and pushing historic legislation on immigration reform and worker rights. Rodríguez led negotiations with the nation’s major grower associations to fashion the agricultural provisions of the bipartisan comprehensive immigration reform bill that passed the U.S. Senate in 2013. He and the UFW worked closely with the White House, meeting with President Obama, over the President’s executive order on immigration issued in November 2014.

Chávez (1927-1993) was a prominent union leader and labor organizer, according History.com.

“Hardened by his early experience as a migrant worker, Chávez founded the National Farm Workers Association in 1962. His union joined with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee in its first strike against grape growers in California, and the two organizations later merged to become the United Farm Workers,” history.com notes. “Stressing nonviolent methods, Chavez drew attention for his causes via boycotts, marches and hunger strikes. Despite conflicts with the Teamsters union and legal barriers, he was able to secure raises and improve conditions for farm workers in California, Texas, Arizona and Florida.” (http://www.history.com/topics/cesar-chavez)

MELON STRIKE MARCH 50th ANNIVERSARY

The city proclamation approved by the Mayor and Edinburg City Council follows:

WHEREAS, In the summer of 1966, hundreds of men, women, and children harvesting cantaloupes in Rio Grande City and Starr County organized with the United Farm Workers and demanded growers raise wages from 40 cents to $1.25 an hour. When their demands were ignored, farm workers walked out on strike and picketed the fields. On the first day of the strike, the Texas Rangers arrested the leader of the Farm Workers; and,

WHEREAS, The workers did not give up. On July 4, 1966, a core group of 30 strikers began a peaceful 400-mile march through South Texas communities to the state Capitol in Austin, gathering support for their cause along the way. On July 7, Mayor Al Ramírez greeted the marchers passing through the City of Edinburg on their way to a mass at the Shrine of Our Lady of San Juan served by the new Bishop Humberto Medeiros, who endorsed their cause to raise wages to $1.25 an hour. (Medeiros would later become a Cardinal in the Catholic Church, serving the Boston region.) They continued through Weslaco, Edcouch, Elsa and continued on their march which took them throughout South Texas towns; and,

WHEREAS, One hot August day, as marchers rested on the side of the road north of New Braunfels, Governor John Connally, Attorney General Waggoner Carr and Speaker of the House Ben Barnes stopped on their dove hunting trip to South Texas to tell them, “No need to continue because we won’t be at the Capitol when you arrive and we will not consider a minimum wage bill in a special session.” That did not deter the marchers. On Labor Day 1966, the strikers, with 10,000 supporters, marched the last four miles from St. Edwards University to the state Capitol; and,

WHEREAS, The strike continued into 1967. Los rinches (the Texas Rangers) and county sheriff’s deputies brutally beat and jailed them in order to break the strike; and,

WHEREAS, As a result of the walkouts, a Texas Minimum Wage law finally passed the Legislature in 1970. In a 1974 ruling (Allee v. Medrano), the U.S. Supreme Court found the Texas Rangers, Starr County Sheriff’s Department and a Starr County justice of the peace conspired to deprive the farm workers of their constitutional rights of free speech and assembly by unlawfully arresting and physically assaulting them. The U.S. Supreme Court in the ruling permanently enjoined the Texas Rangers and its officers from intimidating workers in their organizing efforts; and,

WHEREAS, The Rio Grande Valley melon strike was the beginning of the Chicano movement in Texas; and,

WHEREAS, The United Farm Workers members and supporters erected a building brick-by-brick in San Juan and opened its doors to the community in 1972. The original United Farm Workers union hall in Rio Grande City was in a theater at North Flores and Ringgold streets. Catholic Bishop Humberto Medeiros donated this 10-acre site to the Alliance for Labor Action. On August 31, 1970, the property was transferred to César Chávez’ National Farm Workers Service Center, now the César Chávez Foundation; and,

WHEREAS, The building in San Juan and the farm worker movement continue serving farm workers and other low-income residents to this day in Hidalgo County; and,

NOW, THEREFORE, I, RICHARD H. GARCIA, MAYOR OF THE CITY OF EDINBURG, TEXAS: By the power vested in me by law, do hereby recognize the 50th Anniversary of the MELON STRIKE MARCH. IN WITNESS THEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the City of Edinburg, Texas, a Municipal Corporation, to be affixed on this the 23rd day of August, 2016.

THE CHICANO CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

The Chicano Movement is also known as the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, according to the Library of Congress, which provides the following summary:

The African American Civil Rights Movement was intended by many of its leaders to include all Americans of color struggling for equality, regardless of their origins. In response to the efforts of Dr. Martin Luther King, among others, Hispanic Americans of various backgrounds began organizing their own struggle for civil equality and fairness.

In Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York, Puerto Ricans held marches to protest unequal treatment.

Among Mexican Americans in the Southwest, this struggle came to be known as the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. While each of these groups had similar goals, some of the particular issues they faced were different.

Puerto Ricans could only be regarded as Americans, at least officially, while Mexican Americans faced suspicion that they were not, regardless how many generations of their families had lived in the United States.

Many Puerto Ricans had moved to the cities, and faced problems of urban slums, while this was true for only part of the Mexican American population, many of whom were rural farmers and migrant workers. Many of the issues of Hispanic American rights are as familiar to us today as they were in the 1960s.

In this presentation are songs sung by Puerto Ricans, recorded by Sidney Robertson Cowell in 1939. These recordings pre-date the activist period, but included is a patriotic song of Puerto Rico, “La Tierruca,” sung by Aurora Calderon (select the link for the version illustrated with Library of Congress photographs. (For the field recording without illustrations see this version of “La Tierruca”).

People who had become Americans when western territories were made part of the United States in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War in 1848 felt that the promise of that treaty, to treat colonial Mexican settlers of that territory who chose to remain as U.S. citizens with full civil rights, had never been fulfilled.

Discrimination, educational segregation, voting rights, and ethnic stereotyping were principle issues of the activists, as well as the need for a minimum wage for migrant agricultural workers and citizenship for the children of Mexican-born parents.

The emerging Chicano Civil Rights Movement included strikes and demonstrations with issues expressed through songs in both English and Spanish. This presentation includes a performance by Agustín Lira, who composed and sang activist songs during of the 1960s and 70s along with Quetzal, a group that composes and performs Chicano music related to activism of the 1990s through the present.

Select this link to view the webcast of Augustín Lira and Alma with Quetzal performing songs in Spanish and English, September 14, 2011.

In addition to the songs of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, there are many recordings of Mexican Americans in this presentation, recorded in the 1930s and 1940s. Some of these illustrate the hardships faced by migrant workers of the Dust Bowl era, such as “Yo Cuando era Niño – Mi Padre Querido…” sung by José Suarez.

There are also recordings of the descendants of Spanish settlers in Colorado and New Mexico as well as Cuban Americans in Florida, among other Spanish-speaking groups.

WHERE DOES THE WORD “CHICANO” COME FROM?

According to the Texas State Historical Association (https://www.tshaonline.org/home/), in an article written by Arnoldo De León:

Although the etymology of Chicano is uncertain, linguists and folklorists offer several theories for the origins of the word. According to one explanation, the pre-Columbian tribes in Mexico called themselves Meshicas, and the Spaniards, employing the letter x (which at that time represented a sh and ch sound), spelled it Mexicas. The Indians later referred to themselves as Meshicanos and even as Shicanos, thus giving birth to the term Chicano.

Another theory about the word’s derivation holds that Mexicans and Mexican Americans have historically transferred certain consonants into ch sounds when expressing kinship affection or community fellowship. In this manner, Mexicanos becomes Chicanos. The term has been part of the Mexican-American vocabulary since the early twentieth century, and has conveyed at least two connotations. Mexican Americans of some social standing applied it disparagingly to lower-class Mexicans, but as time passed, adolescents and young adults (usually males) used Chicano as an affirmative label expressing camaraderie and commonality of experience.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the designation gained mainstream prominence because of a civil-rights groundswell (see CIVIL RIGHTS) within Mexican-American communities. The catalyst in Texas was a dramatic farmworkers’ march during the summer of 1966; the march from South Texas to Austin turned media attention to the plight of the state’s army of agricultural field hands.

Inspired by the courage of the farmworkers, by the California strikes led by César Chávez, and by the Anglo-American youth revolt of the period, many Mexican-American university students came to participate in a crusade for social betterment that was known as the Chicano movement. They used Chicano to denote their rediscovered heritage, their youthful assertiveness, and their militant agenda. Though these students and their supporters used Chicano to refer to the entire Mexican-American population, they understood it to have a more direct application to the politically active parts of the Tejanoqv community.

Almost from the initial mainstream appearance of Chicano during the 1960s, the Spanish-speaking population resented the word’s broad usage, and this displeasure led to the cognomen’s decline in general discourse by the late 1970s. The older generation remembered the word’s earlier disparaging implications, and other Mexican Americans felt uncomfortable using Chicano in formal conversation. Most significantly, many Mexican Americans rejected the way self-styled Chicanos had taken the expression from its in-group folkloric context and appropriated it for common dialogue. It was this violation of folkloric norms that produced the word’s repudiation from within by the early 1980s. Mexican Americans, Hispanics, or Latinos took its place. Chicano, however, remained a part of the overall in-group lexicon.

••••••

For more information on the Edinburg Economic Development Corporation and the City of Edinburg, please log on to http://edinburgedc.com or to http://www.facebook.com/edinburgedc